Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus and Christian kingdoms circa 1000 AD, at the apogee of Almanzor

| History of Al-Andalus |

|---|

|

Muslim conquest (711–732) |

|

Umayyads of Córdoba (756–1031) |

|

First Taifa period (1009–1110) |

|

Almoravid rule (1085–1145) |

|

Second Taifa period (1140–1203) |

|

Almohad rule (1147–1238) |

|

Third Taifa period (1232–1287) |

|

Emirate of Granada (1238–1492) |

| Related articles |

Following the Umayyad conquest of Hispania, al-Andalus, then at its greatest extent, was divided into five administrative units, corresponding roughly to modern Andalusia, Portugal and Galicia, Castile and León, Navarre, Aragon, the County of Barcelona, and Septimania.[4] As a political domain, it successively constituted a province of the Umayyad Caliphate, initiated by the Caliph Al-Walid I (711–750); the Emirate of Córdoba (c. 750–929); the Caliphate of Córdoba (929–1031); and the Caliphate of Córdoba's taifa (successor) kingdoms. Rule under these kingdoms led to a rise in cultural exchange and cooperation between Muslims and Christians. Christians and Jews were subject to a special tax called Jizya, to the state, which in return provided internal autonomy in practicing their religion and offered the same level of protections by the Muslim rulers.[5]

Under the Caliphate of Córdoba, al-Andalus was a beacon of learning, and the city of Córdoba, the largest in Europe, became one of the leading cultural and economic centres throughout the Mediterranean Basin, Europe, and the Islamic world. Achievements that advanced Islamic and Western science came from al-Andalus, including major advances in trigonometry (Geber), astronomy (Arzachel), surgery (Abulcasis), pharmacology (Avenzoar),[6] agronomy (Ibn Bassal and Abū l-Khayr al-Ishbīlī),[7] and other fields. Al-Andalus became a major educational center for Europe and the lands around the Mediterranean Sea as well as a conduit for culture and science between the Islamic and Christian worlds.[6]

For much of its history, al-Andalus existed in conflict with Christian kingdoms to the north. After the fall of the Umayyad caliphate, al-Andalus was fragmented into minor states and principalities. Attacks from the Christians intensified, led by the Castilians under Alfonso VI. The Almoravid empire intervened and repelled the Christian attacks on the region, deposing the weak Andalusi Muslim princes and included al-Andalus under direct Berber rule. In the next century and a half, al-Andalus became a province of the Berber Muslim empires of the Almoravids and Almohads, both based in Marrakesh.

Ultimately, the Christian kingdoms in the north of the Iberian Peninsula overpowered the Muslim states to the south. In 1085, Alfonso VI captured Toledo, starting a gradual decline of Muslim power. With the fall of Córdoba in 1236, most of the south quickly fell under Christian rule and the Emirate of Granada became a tributary state of the Kingdom of Castile two years later. In 1249, the Portuguese Reconquista culminated with the conquest of the Algarve by Afonso III, leaving Granada as the last Muslim state on the Iberian Peninsula. Finally, on January 2, 1492,[8] Emir Muhammad XII surrendered the Emirate of Granada to Queen Isabella I of Castile, completing the Christian Reconquista of the peninsula. Although al-Andalus ended as a political entity, the nearly eight centuries of Islamic rule which preceded and accompanied the early formation of the Spanish nation-state and identity has left a profound effect on the country's culture and language, particularly in Andalusia.[9]

Contents

Name

The toponym al-Andalus is first attested by inscriptions on coins minted in 716 by the new Muslim government of Iberia. These coins, called dinars, were inscribed in both Latin and Arabic.[10][11] The etymology of the name "al-Andalus" has traditionally been derived from the name of the Vandals; however, proposals since the 1980s have challenged this contention. In 1986, Joaquín Vallvé proposed that "al-Andalus" was a corruption of the name Atlantis,[12] Halm in 1989 derived the name from a Gothic term, *landahlauts,[13] and in 2002, Bossong suggested its derivation from a pre-Roman substrate.[14]History

Province of the Umayyad Caliphate

Most of the Iberian peninsula became part of the expanding Umayyad Empire, under the name of al-Andalus. It was organized as a province subordinate to Ifriqiya, so, for the first few decades, the governors of al-Andalus were appointed by the emir of Kairouan, rather than the Caliph in Damascus. The regional capital was set at Córdoba, and the first influx of Muslim settlers was widely distributed.

The small army Tariq led in the initial conquest consisted mostly of Berbers, while Musa's largely Arab force of over 12,000 soldiers was accompanied by a group of mawālī (Arabic, موالي), that is, non-Arab Muslims, who were clients of the Arabs. The Berber soldiers accompanying Tariq were garrisoned in the centre and the north of the peninsula, as well as in the Pyrenees,[15] while the Berber colonists who followed settled in all parts of the country – north, east, south and west.[16] Visigothic lords who agreed to recognize Muslim suzerainty were allowed to retain their fiefs (notably, in Murcia, Galicia, and the Ebro valley). Resistant Visigoths took refuge in the Cantabrian highlands, where they carved out a rump state, the Kingdom of Asturias.

The province of al-Andalus in 750

Interior of the Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba

formerly the Great Mosque of Córdoba. The original mosque (742), since

much enlarged, was built on the site of the Visigothic Christian 'Saint

Vincent basilica' (600).

In 740, a Berber Revolt erupted in the Maghreb (North Africa). To put down the rebellion, the Umayyad Caliph Hisham dispatched a large Arab army, composed of regiments (Junds) of Bilad Ash-Sham,[17] to North Africa. But the great Syrian army was crushed by the Berber rebels at the Battle of Bagdoura (in Morocco). Heartened by the victories of their North African brethren, the Berbers of al-Andalus quickly raised their own revolt. Berber garrisons in northern Spain mutinied, deposed their Arab commanders, and organized a large rebel army to march against the strongholds of Toledo, Cordoba, and Algeciras.

In 741, Balj b. Bishr led a detachment of some 10,000 of the Arabic-speaking troops referred to as "the Syrians" across the straits.[18] The Arab governor of al-Andalus, joined by this force, crushed the Berber rebels in a series of ferocious battles in 742. However, a quarrel immediately erupted between the Syrian commanders and the Andalusi, the so-called "original Arabs" of the earlier contingents. The Syrians defeated them at the hard-fought Battle of Aqua Portora in August 742 but were too few to impose themselves on the province.

The quarrel was settled in 743 when Abū l-Khaṭṭār al-Ḥusām, the new governor of al-Andalus, assigned the Syrians to regimental fiefs across al-Andalus[19] – the Damascus jund was established in Elvira (Granada), the Jordan jund in Rayyu (Málaga and Archidona), the Jund Filastin in Medina-Sidonia and Jerez, the Emesa (Hims) jund in Seville and Niebla, and the Qinnasrin jund in Jaén. The Egypt jund was divided between Beja (Alentejo) in the west and Tudmir (Murcia) in the east.[20] The arrival of the Syrians substantially increased the Arab element in the Iberian peninsula and helped strengthen the Muslim hold on the south. However, at the same time, unwilling to be governed, the Syrian junds carried on an existence of autonomous feudal anarchy, severely destabilizing the authority of the governor of al-Andalus.

Portrait of Abd al-Rahman I

These disturbances and disorders also allowed the Franks, now under the leadership of Pepin the Short, to invade the strategic strip of Septimania in 752, hoping to deprive al-Andalus of an easy launching pad for raids into Francia. After a lengthy siege, the last Arab stronghold, the citadel of Narbonne, finally fell to the Franks in 759. Al-Andalus was sealed off at the Pyrenees.[21]

The third consequence of the Berber revolt was the collapse of the authority of the Damascus Caliphate over the western provinces. With the Umayyad Caliphs distracted by the challenge of the Abbasids in the east, the western provinces of the Maghreb and al-Andalus spun out of their control. From around 745, the Fihrids, an illustrious local Arab clan descended from Oqba ibn Nafi al-Fihri, seized power in the western provinces and ruled them almost as a private family empire of their own – Abd al-Rahman ibn Habib al-Fihri in Ifriqiya and Yūsuf al-Fihri in al-Andalus. The Fihrids welcomed the fall of the Umayyads in the east, in 750, and sought to reach an understanding with the Abbasids, hoping they might be allowed to continue their autonomous existence. But when the Abbasids rejected the offer and demanded submission, the Fihrids declared independence and, probably out of spite, invited the deposed remnants of the Umayyad clan to take refuge in their dominions. It was a fateful decision that they soon regretted, for the Umayyads, the sons and grandsons of caliphs, had a more legitimate claim to rule than the Fihrids themselves. Rebellious-minded local lords, disenchanted with the autocratic rule of the Fihrids, conspired with the arriving Umayyad exiles.

Umayyad Emirate and Caliphate of Córdoba

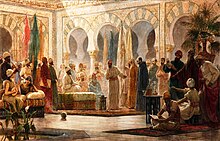

Abd-ar-Rahman III and his court receiving an ambassador in Medina Azahara, Còrdoba

For the next century and a half, his descendants continued as emirs of Córdoba with nominal control over the rest of al-Andalus and sometimes parts of western North Africa, but with real control, particularly over the marches along the Christian border, vacillating depending on the competence of the individual emir. Indeed, the power of emir Abdallah ibn Muhammad (circa 900) did not extend beyond Córdoba itself. But his grandson Abd-al-Rahman III, who succeeded him in 912, not only rapidly restored Umayyad power throughout al-Andalus but extended it into western North Africa as well. In 929 he proclaimed himself Caliph, elevating the emirate to a position competing in prestige not only with the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad but also the Fatimid caliph in Tunis—with whom he was competing for control of North Africa.

The Caliphate of Cordoba in the early 10th century

Muslims and non-Muslims often came from abroad to study in the famous libraries and universities of al-Andalus, mainly after the reconquest of Toledo in 1085 and the establishment of translation institutions such as the Toledo School of Translators. The most noted of those was Michael Scot (c. 1175 to c. 1235), who took the works of Ibn Rushd ("Averroes") and Ibn Sina ("Avicenna") to Italy. This transmission of ideas remains one of the greatest in history, significantly affecting the formation of the European Renaissance.[26]

Taifas period

Gold dinar minted in Córdoba during the reign of Hisham II

Almoravids, Almohads, and Marinids

Map showing the extent of the Almoravid empire

Expansion of the Almohad state in the 12th century

The Almoravids were succeeded by the Almohads, another Berber dynasty, after the victory of Abu Yusuf Ya'qub al-Mansur over the Castilian Alfonso VIII at the Battle of Alarcos in 1195. In 1212, a coalition of Christian kings under the leadership of the Castilian Alfonso VIII defeated the Almohads at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa. The Almohads continued to rule Al-Andalus for another decade, though with much reduced power and prestige. The civil wars following the death of Abu Ya'qub Yusuf II rapidly led to the re-establishment of taifas. The taifas, newly independent but now weakened, were quickly conquered by Portugal, Castile, and Aragon. After the fall of Murcia (1243) and the Algarve (1249), only the Emirate of Granada survived as a Muslim state, and only as a tributary of Castile until 1492. Most of its tribute was paid in gold that was carried to Iberia from present-day Mali and Burkina Faso through the merchant routes of the Sahara.

The last Muslim threat to the Christian kingdoms was the rise of the Marinids in Morocco during the 14th century. They took Granada into their sphere of influence and occupied some of its cities, like Algeciras. However, they were unable to take Tarifa, which held out until the arrival of the Castilian Army led by Alfonso XI. The Castilian king, with the help of Afonso IV of Portugal and Peter IV of Aragon, decisively defeated the Marinids at the Battle of Río Salado in 1340 and took Algeciras in 1344. Gibraltar, then under Granadian rule, was besieged in 1349–50. Alfonso XI and most of his army perished by the Black Death. His successor, Peter of Castile, made peace with the Muslims and turned his attention to Christian lands, starting a period of almost 150 years of rebellions and wars between the Christian states that secured the survival of Granada.

Emirate of Granada, its fall, and aftermath

A painting of Muhammad XII of Granada, last Muslim sultan in Spain. Date of this painting and its current location are unknown.

Muhammad XII's family in the Alhambra moments after the fall of Granada, by Manuel Gómez-Moreno González, c. 1880

By this time Muslims in Castile numbered half a million. After the fall, "100,000 had died or been enslaved, 200,000 emigrated, and 200,000 remained as the residual population. Many of the Muslim elite, including Muhammad XII, who had been given the area of the Alpujarras mountains as a principality, found life under Christian rule intolerable and passed over into North Africa."[33] Under the conditions of the Capitulations of 1492, the Muslims in Granada were to be allowed to continue to practice their religion.

Mass forced conversions of Muslims in 1499 led to a revolt that spread to Alpujarras and the mountains of Ronda; after this uprising the capitulations were revoked.[34] In 1502 the Catholic Monarchs decreed the forced conversion of all Muslims living under the rule of the Crown of Castile,[35] although in the kingdoms of Aragon and Valencia (both now part of Spain) the open practice of Islam was allowed until 1526.[36] Descendants of the Muslims were subject to expulsions from Spain between 1609 and 1614 (see Expulsion of the Moriscos).[37] The last mass prosecution against Moriscos for crypto-Islamic practices occurred in Granada in 1727, with most of those convicted receiving relatively light sentences. From then on, indigenous Islam is considered to have been extinguished in Spain.[38]

Society

Clothing of al-Andalus in the 15th century, during the Emirate of Granada

The ethnic structure of al-Andalus consisted of Arabs at the top of the social scale followed by, in descending order, Berbers, Muladies, Mozarabes, and Jews.[40] Each of these communities inhabited distinct neighborhoods in the cities. In the 10th century a massive conversion of Christians took place, and muladies (Muslims of native Iberian origin), formed the majority of Muslims. The Muladies had spoken in a Romance dialect of Latin called Mozarabic while increasingly adopting the Arabic language, which eventually evolved into the Andalusi Arabic in which Muslims, Jews, and Christians became monolingual in the last surviving Muslim state in the Iberian Peninsula, the Emirate of Granada (1230-1492). Eventually, the Muladies, and later the Berber tribes, adopted an Arabic identity like the majority of subject people in Egypt, the Levant, Mesopotamia, and North Africa. Muladies, together with other Muslims, comprised eighty percent of the population of al-Andalus by 1100.[41][42] Mozarabs were Christians who had long lived under Muslim and Arab rule, adopting many Arab customs, art, and words, while still maintaining their Christian and Latin rituals and their own Romance languages.

The Jewish population worked mainly as tax collectors, in trade, or as doctors or ambassadors. At the end of the 15th century there were about 50,000 Jews in Granada and roughly 100,000 in the whole of Islamic Iberia.[43]

Non-Muslims under the Caliphate

A Christian and a Muslim playing chess in 13th-century al-Andalus

The longest period of relative tolerance began after 912 with the reign of Abd-ar-Rahman III and his son, Al-Hakam II, when the Jews of al-Andalus prospered, devoting themselves to the service of the Caliphate of Córdoba, to the study of the sciences, and to commerce and industry, especially trading in silk and slaves, in this way promoting the prosperity of the country. Southern Iberia became an asylum for the oppressed Jews of other countries.[47][48]

Under the Almoravids and the Almohads there may have been intermittent persecution of Jews,[49] but sources are extremely scarce and do not give a clear picture, though the situation appears to have deteriorated after 1160.[50] Muslim pogroms against Jews in al-Andalus occurred in Córdoba (1011) and in Granada (1066).[51][52][53] However, massacres of dhimmis are rare in Islamic history.[54]

The Almohads, who had taken control of the Almoravids' Maghribi and Andalusi territories by 1147,[55] far surpassed the Almoravides in fundamentalist outlook, and they treated the non-Muslims harshly. Faced with the choice of either death or conversion, many Jews and Christians emigrated.[56][57] Some, such as the family of Maimonides, fled east to more tolerant Muslim lands.[56]

Culture

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2017)

|

From the earliest days, the Umayyads wanted to be seen as intellectual rivals to the Abbasids, and for Córdoba to have libraries and educational institutions to rival Baghdad's. Although there was a clear rivalry between the two powers, there was freedom to travel between the two caliphates,[citation needed] which helped spread new ideas and innovations over time.

Art and architecture

The Alhambra, constructed by the orders of the first Nasrid emir Ibn al-Ahmar in the 13th century

The decoration within the palace comes from the last great period of Andalusian art in Granada, with little of the Byzantine influence of contemporary Abbasid architecture.[59] Artists endlessly reproduced the same forms and trends, creating a new style that developed over the course of the Nasrid Dynasty using elements created and developed during the centuries of Muslim rule on the Peninsula, including the Caliphate horseshoe arch, the Almohad sebka (a grid of rhombuses), the Almoravid palm, and unique combinations of these, as well as innovations such as stilted arches and muqarnas (stalactite ceiling decorations). Columns and muqarnas appear in several chambers, and the interiors of numerous palaces are decorated with arabesques and calligraphy. The arabesques of the interior are ascribed to, among other sultans, Yusuf I, Muhammed V, and Ismail I, Sultan of Granada.

Philosophy

This section includes a list of references, related reading or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (July 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

Al-Andalus philosophy

The historian Said al-Andalusi wrote that Caliph Abd-ar-Rahman III had collected libraries of books and granted patronage to scholars of medicine and "ancient sciences". Later, al-Mustansir (Al-Hakam II) went yet further, building a university and libraries in Córdoba. Córdoba became one of the world's leading centres of medicine and philosophical debate.

Averroes, founder of the Averroism school of philosophy, was influential in the rise of secular thought in Western Europe. Detail from Triunfo de Santo Tomás by Andrea Bonaiuto, 14th century

A prominent follower of al-Majriti was the philosopher and geometer Abu al-Hakam al-Kirmani who was followed, in turn, by Abu Bakr Ibn al-Sayigh, usually known in the Arab world as Ibn Bajjah, "Avempace".

The al-Andalus philosopher Averroes (1126–1198) was the founder of the Averroism school of philosophy, and his works and commentaries influenced medieval thought in Western Europe[citation needed]. Another influential al-Andalus philosopher was Ibn Tufail.

Jewish philosophy and culture

Jewish Street Sign in Toledo, Spain

Homosexuality

This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (July 2018)

|

See also

- Gharb Al-Andalus

- Almohad dynasty

- Moors

- Almoravids

- Arab diaspora

- Islam and anti-Semitism in Iberia

- History of Islam

- History of the Jews under Muslim rule

- Hispanic and Latino Muslims

- Islamic Golden Age

- Islam in Spain

- La Convivencia

- Moorish Gibraltar

- Morisco

- Mozarab

- Muladi

- Muslim conquests

- Social and cultural exchange in Al-Andalus

- Timeline of the Muslim presence in the Iberian peninsula

- Kemal Reis

- List of Moorish writers

History

|

|

|

Footnotes

- Daniel Eisenberg (2003). "Homosexuality". In E. Michael Gerli, Samuel G. Armistead. Medieval Iberia. Taylor & Francis. p. 398. ISBN 978-0-415-93918-8.

References

- Glick, Thomas (1999). "Islamic and Christian Spain in the Early Middle Ages: Comparative Perspectives on Social and Cultural Formation". Retrieved 23 October 2011.[permanent dead link]

Bibliography

- Alfonso, Esperanza, 2007. Islamic Culture Through Jewish Eyes: al-Andalus from the Tenth to Twelfth Century. NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-43732-5

- Al-Djazairi, Salah Eddine 2005. The Hidden Debt to Islamic Civilisation. Manchester: Bayt Al-Hikma Press. ISBN 0-9551156-1-2

- Bossong, Georg. 2002. “Der Name Al-Andalus: Neue Überlegungen zu einem alten Problem”, Sounds and Systems: Studies in Structure and Change. A Festschrift for Theo Vennemann, eds. David Restle & Dietmar Zaefferer. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 149–164. (In German) Also available online: see External Links below.

- Cohen, Mark. 1994. Under Crescent and Cross: The Jews in the Middle Ages. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01082-X

- Collins, Roger. 1989. The Arab Conquest of Spain, 710–797, Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-19405-3

- Dodds, Jerrilynn D. (1992). Al-Andalus: the art of Islamic Spain. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9780870996368.

- Fernandez-Morera, Dario. 2016. The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise: Muslims, Christians, and Jews under Islamic Rule in Medieval Spain. NY: Intercollegiate Studies Institute. ISBN 978-1610170956

- Frank, Daniel H. & Leaman, Oliver. 2003. The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Jewish Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-65574-9

- Gerli, E. Michael, ed., 2003. Medieval Iberia: An Encyclopedia. NY: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-93918-6

- Halm, Heinz. 1989. “Al-Andalus und Gothica Sors”, Der Islam 66:252–263.

- Hamilton, Michelle M., Sarah J. Portnoy, and David A. Wacks, eds. 2004. Wine, Women, and Song: Hebrew and Arabic Literature in Medieval Iberia. Newark, Del.: Juan de la Cuesta Hispanic Monographs.

- Harzig, Christiane, Dirk Hoerder, and Adrian Shubert. 2003. The Historical Practice in Diversity. Berghahn Books. ISBN 1-57181-377-2

- Jayyusi, Salma Khadra. 1992. The Legacy of Muslim Spain, 2 vols. Leiden–NY–Cologne: Brill [chief consultant to the editor, Manuela Marín].

- Kennedy, Hugh. 1996. Muslim Spain and Portugal: A Political History of al-Andalus, Longman. ISBN 0-582-49515-6

- Kraemer, Joel. 1997. “Comparing Crescent and Cross (book review)”, The Journal of Religion 77, no. 3 (1997): 449–454.

- Kraemer, Joel. 2005. “Moses Maimonides: An Intellectual Portrait”, The Cambridge Companion to Maimonides, ed. Kenneth Seeskin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-81974-1

- Kraemer, Joel. 2008. Maimonides: the Life and World of One of Civilization's Greatest Minds. NY: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-51199-X

- Lafuente y Alcántara, Emilio, trans. 1867. Ajbar Machmua (colección de tradiciones): crónica anónima del siglo XI, dada a luz por primera vez, traducida y anotada. Madrid: Real Academia de la Historia y Geografía. In Spanish and Arabic. Also available in the public domain online, see External Links.

- Luscombe, David and Jonathan Riley-Smith, eds. 2004. The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 4, c. 1024 – c. 1198, Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-41411-3

- Marcus, Ivan G., “Beyond the Sephardic mystique”, Orim, vol. 1 (1985): 35-53.

- Marín, Manuela, ed. 1998. The Formation of Al-Andalus, vol. 1: History and Society. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 0-86078-708-7

- Menocal, Maria Rosa. 2002. Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews, and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain. Boston: Little, Brown and Company; London: Back Bay Books. ISBN 0-316-16871-8

- Monroe, James T. 1970. Islam and the Arabs in Spanish scholarship: (Sixteenth century to the present). Leiden: Brill.

- Monroe, James T. 1974. Hispano-Arabic Poetry: A Student Anthology. Berkeley, Cal.: University of California Press.

- Netanyahu, Benzion. 1995. The Origins Of The Inquisition in Fifteenth Century Spain. NY: Random House ISBN 0-679-41065-1

- O'Callaghan, Joseph F. 1975. A History of Medieval Spain. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9264-5

- Omaar, Rageh. 2005. An Islamic History of Europe. video documentary, BBC 4, August 2005.

- Reilly, Bernard F. 1993. The Medieval Spains. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39741-3

- Roth, Norman. 1994. Jews, Visigoths and Muslims in Medieval Spain: Cooperation and Conflict. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-06131-2

- Sanchez-Albornoz, Claudio. 1974. El Islam de España y el Occidente. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe. Colección Austral; 1560. [Originally published in 1965 in the conference proceedings, L'occidente e l'islam nell'alto medioevo: 2-8 aprile 1964, 2 vols. Spoleto: Centro Italiano di studi sull'Alto Medioevo. Series: Settimane di studio del Centro Italiano di studi sull'Alto Medioevo; 12. Vol. 1:149–308.]

- Schorsch, Ismar, 1989. “The myth of Sephardic supremacy”, The Leo Baeck Institute Yearbook 34 (1989): 47–66.

- Stavans, Ilan. 2003. The Scroll and the Cross: 1,000 Years of Jewish-Hispanic Literature. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-92930-X

- The Art of medieval Spain, A.D. 500-1200. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1993. ISBN 0870996851.

- Wasserstein, David J. 1995. “Jewish élites in Al-Andalus”, The Jews of Medieval Islam: Community, Society and Identity, ed. Daniel Frank. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-10404-6

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Al-Andalus. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Al-Andalus |

- Photocopy of the Ajbar Machmu'a, translated by Lafuente 1867

- The routes of al-Andalus (from the UNESCO web site)

- The Library of Iberian Resources Online

- Al-Andalus Chronology and Photos

- Christian Martyrs in Muslim Spain by Kenneth Baxter Wolf

- The Musical Legacy of Al-Andalus – historical maps, photos, and music showing the Great Mosque of Córdoba and related movements of people and culture over time

- Patricia, Countess Jellicoe, 1992, The Art of Islamic Spain, Saudi Aramco World

- "Cities of Light: The Rise and Fall of Islamic Spain" (documentary film)

- Al-Andalus: the art of Islamic Spain, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF)

- History of the Spanish Muslims, by Reinhart Dozy, in French

Categories:

- Al-Andalus

- Former countries on the Iberian Peninsula

- Former empires in Europe

- Former Muslim countries in Europe

- History of Andalusia

- Medieval Morocco

- History of Portugal by polity

- Invasions of Europe

- Islam in Gibraltar

- Islam in Portugal

- Islam in Spain

- Medieval Islam

- Medieval Portugal

- Medieval Spain

- Moors

- Muslim empires

- States and territories established in the 710s

- States and territories disestablished in 1492

- 711 establishments

- 8th-century establishments in Portugal

- 8th-century establishments in Spain

- 1492 disestablishments in Spain

- 1st millennium in Spain

- 2nd millennium in Spain

- Subdivisions of the Umayyad Caliphate

Languages

"Los arabes y musulmanes de la Edad Media aplicaron el nombre de Al-Andalus a todas aquellas tierras que habian formado parte del reino visigodo: la Peninsula Ibérica y la Septimania ultrapirenaica." ("The Arabs and Muslims from the Middle Ages used the name of al-Andalus for all those lands that were formerly part of the Visigothic kingdom: the Iberian Peninsula and Septimania")

Only a few years after the Islamic conquest of Spain, Al-Andalus appears in coin inscriptions as the Arabic equivalent of Hispania. The traditionally held view that the etymology of this name has to do with the Vandals is shown to have no serious foundation. The phonetic, morphosyntactic, and historical problems connected with this etymology are too numerous. Moreover, the existence of this name in various parts of central and northern Spain proves that Al-Andalus cannot be derived from this Germanic tribe. It was the original name of the Punta Marroquí cape near Tarifa; very soon, it became generalized to designate the whole Peninsula. Undoubtedly, the name is of Pre-Indo-European origin. The parts of this compound (anda and luz) are frequent in the indigenous toponymy of the Iberian Peninsula.

Comments

Post a Comment