Islamic attitudes towards science

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

Scientists of medieval Muslim civilization (e.g. Ibn al-Haytham) made many contributions to modern science.[5][6][7] This fact is celebrated in the Muslim world today.[8] At the same time, concerns have been raised about the lack of scientific literacy in parts of the modern Muslim world.[9]

Some Muslim writers have claimed that the Qur'an made prescient statements about scientific phenomena that were later confirmed by scientific research for instance as regards to the structure of the embryo, our solar system, and the creation of the universe.[10][11]

Contents

Overview

According to M. Shamsher Ali, there are around 750 verses in the Quran dealing with natural phenomena. Many verses of the Qur'an ask mankind to study nature, and this has been interpreted to mean an encouragement for scientific inquiry.[2] The investigation of the truth is one of the main messages of the Qur'an.[2][additional citation(s) needed] historical Islamic scientists like Al-Biruni and Al-Battani derived their inspiration from verses of the Quran. Mohammad Hashim Kamali has stated that "scientific observation, experimental knowledge and rationality" are the primary tools with which humanity can achieve the goals laid out for it in the Quran.[12] Ziauddin Sardar built a case for Muslims having developed the foundations of modern science, by highlighting the repeated calls of the Quran to observe and reflect upon natural phenomenon.[13] "The 'scientific method,' as it is understood today, was first developed by Muslim scientists" like Ibn al-Haytham and Al-Biruni, along with numerous other Muslim scientists.The astrophysicist Nidhal Guessoum while being highly critical of pseudo-scientific claims made about the Quran, has highlighted the encouragement for sciences that the Quran provides by developing "the concept of knowledge.".[14] He writes: "The Qur'an draws attention to the danger of conjecturing without evidence (And follow not that of which you have not the (certain) knowledge of... 17:36) and in several different verses asks Muslims to require proofs (Say: Bring your proof if you are truthful 2:111), both in matters of theological belief and in natural science." Guessoum cites Ghaleb Hasan on the definition of "proof" according the Quran being "clear and strong... convincing evidence or argument." Also, such a proof cannot rely on an argument from authority, citing verse 5:104. Lastly, both assertions and rejections require a proof, according to verse 4:174.[15] Ismail al-Faruqi and Taha Jabir Alalwani are of the view that any reawakening of the Muslim civilization must start with the Quran; however, the biggest obstacle on this route is the "centuries old heritage of tafseer (exegesis) and other classical disciplines" which inhibit a "universal, epistemiological and systematic conception" of the Quran's message.[16] The philosopher Muhammad Iqbal considered the Quran's methodology and epistemology to be empirical and rational.[17]

The physicist Abdus Salam believed there is no contradiction between Islam and the discoveries that science allows humanity to make about nature and the universe; and that the Quran and the Islamic spirit of study and rational reflection was the source of extraordinary civilizational development. Salam highlights, in particular, the work of Ibn al-Haytham and Al-Biruni as the pioneers of empiricism who introduced the experimental approach, breaking way from Aristotle's influence, and thus giving birth to modern science. Salam differentiated between metaphysics and physics, and advised against empirically probing certain matters on which "physics is silent and will remain so," such as the doctrine of "creation from nothing" which in Salam's view is outside the limits of science and thus "gives way" to religious considerations.[18]

The religion Islam has its own world view system including beliefs about "ultimate reality, epistemology, ontology, ethics, purpose, etc."[19] Muslims believe that the Qur'an is the final revelation of God for the guidance of humankind. Science is the pursuit of knowledge and understanding of the natural and social world following a systematic methodology based on evidence.[20] It is a system of acquiring knowledge based on empiricism, experimentation and methodological naturalism, as well as to the organized body of knowledge human beings have gained by such research. Scientists maintain that scientific investigation needs to adhere to the scientific method, a process for evaluating empirical knowledge that explains observable events without recourse to supernatural notions.

In Islam, nature is not seen as something separate but as an integral part of a holistic outlook on God, humanity, the world and the cosmos. These links imply a sacred aspect to Muslims' pursuit of scientific knowledge, as nature itself is viewed in the Qur'an as a compilation of signs pointing to the Divine.[21] It was with this understanding that the pursuit of science, especially prior to the colonization of the Muslim world, was respected in Islamic civilizations.[22]

History

Classical science in the Muslim world

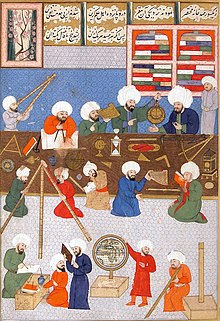

Work in the observatorium of Taqi al-Din

A number of modern scholars such as Fielding H. Garrison, Sultan Bashir Mahmood, Hossein Nasr consider modern science and the scientific method to have been greatly inspired by Muslim scientists who introduced a modern empirical, experimental and quantitative approach to scientific inquiry.[citation needed] Certain advances made by medieval Muslim astronomers, geographers and mathematicians were motivated by problems presented in Islamic scripture, such as Al-Khwarizmi's (c. 780–850) development of algebra in order to solve the Islamic inheritance laws,[24] and developments in astronomy, geography, spherical geometry and spherical trigonometry in order to determine the direction of the Qibla, the times of Salah prayers, and the dates of the Islamic calendar.[25]

The increased use of dissection in Islamic medicine during the 12th and 13th centuries was influenced by the writings of the Islamic theologian, Al-Ghazali, who encouraged the study of anatomy and use of dissections as a method of gaining knowledge of God's creation.[26] In al-Bukhari's and Muslim's collection of sahih hadith it is said: "There is no disease that Allah has created, except that He also has created its treatment." (Bukhari 7-71:582). This culminated in the work of Ibn al-Nafis (1213–1288), who discovered the pulmonary circulation in 1242 and used his discovery as evidence for the orthodox Islamic doctrine of bodily resurrection.[27] Ibn al-Nafis also used Islamic scripture as justification for his rejection of wine as self-medication.[28] Criticisms against alchemy and astrology were also motivated by religion, as orthodox Islamic theologians viewed the beliefs of alchemists and astrologers as being superstitious.[29]

Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (1149–1209), in dealing with his conception of physics and the physical world in his Matalib, discusses Islamic cosmology, criticizes the Aristotelian notion of the Earth's centrality within the universe, and "explores the notion of the existence of a multiverse in the context of his commentary," based on the Qur'anic verse, "All praise belongs to God, Lord of the Worlds." He raises the question of whether the term "worlds" in this verse refers to "multiple worlds within this single universe or cosmos, or to many other universes or a multiverse beyond this known universe." On the basis of this verse, he argues that God has created more than "a thousand thousand worlds (alfa alfi 'awalim) beyond this world such that each one of those worlds be bigger and more massive than this world as well as having the like of what this world has."[30] Ali Kuşçu's (1403–1474) support for the Earth's rotation and his rejection of Aristotelian cosmology (which advocates a stationary Earth) was motivated by religious opposition to Aristotle by orthodox Islamic theologians, such as Al-Ghazali.[31][32]

According to many historians, science in the Muslim civilization flourished during the Middle Ages, but began declining at some time around the 14th[33] to 16th[23] centuries. At least some scholars blame this on the "rise of a clerical faction which froze this same science and withered its progress."[34] Examples of conflicts with prevailing interpretations of Islam and science – or at least the fruits of science – thereafter include the demolition of Taqi al-Din's great Istanbul observatory of Taqi al-Din in Galata, "comparable in its technical equipment and its specialist personnel with that of his celebrated contemporary, the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe." But while Brahe's observatory "opened the way to a vast new development of astronomical science," Taqi al-Din's was demolished by a squad of Janissaries, "by order of the sultan, on the recommendation of the Chief Mufti," sometime after 1577 CE.[34][35]

Arrival of modern science in the Muslim world

This article contains too many or too-lengthy quotations for an encyclopedic entry. (March 2008)

|

- Some rejected modern science as corrupt foreign thought, considering it incompatible with Islamic teachings, and in their view, the only remedy for the stagnancy of Islamic societies would be the strict following of Islamic teachings.[36]

- Other thinkers in the Muslim world saw science as the only source of real enlightenment and advocated the complete adoption of modern science. In their view, the only remedy for the stagnation of Muslim societies would be the mastery of modern science and the replacement of the religious worldview by the scientific worldview.

- The majority of faithful Muslim scientists tried to adapt Islam to the findings of modern science; they can be categorized in the following subgroups: (a) Some Muslim thinkers attempted to justify modern science on religious grounds. Their motivation was to encourage Muslim societies to acquire modern knowledge and to safeguard their societies from the criticism of Orientalists and Muslim intellectuals. (b) Others tried to show that all important scientific discoveries had been predicted in the Qur'an and Islamic tradition and appealed to modern science to explain various aspects of faith. (c) Yet other scholars advocated a re-interpretation of Islam. In their view, one must try to construct a new theology that can establish a viable relation between Islam and modern science. The Indian scholar, Sayyid Ahmad Khan, sought a theology of nature through which one could re-interpret the basic principles of Islam in the light of modern science. (d) Then there were some Muslim scholars who believed that empirical science had reached the same conclusions that prophets had been advocating several thousand years ago. The revelation had only the privilege of prophecy.

- Finally, some Muslim philosophers separated the findings of modern science from its philosophical attachments. Thus, while they praised the attempts of Western scientists for the discovery of the secrets of nature, they warned against various empiricist and materialistic interpretations of scientific findings. Scientific knowledge can reveal certain aspects of the physical world, but it should not be identified with the alpha and omega of knowledge. Rather, it has to be integrated into a metaphysical framework—consistent with the Muslim worldview—in which higher levels of knowledge are recognized and the role of science in bringing us closer to God is fulfilled.[19]

Decline

In the early twentieth century, Shia ulema forbade the learning of foreign languages and dissection of human bodies in the medical school in Iran.[37]In recent years, the lagging of the Muslim world in science is manifest in the disproportionately small amount of scientific output as measured by citations of articles published in internationally circulating science journals, annual expenditures on research and development, and numbers of research scientists and engineers.[38] Concern has been raised that the contemporary Muslim world suffers from scientific illiteracy.[9] Skepticism of science among some Muslims is reflected in issues such as resistance in Muslim northern Nigeria to polio inoculation, which some believe is "an imaginary thing created in the West or it is a ploy to get us to submit to this evil agenda."[39] Also, in Pakistan, a small number of post-graduate physics students have been known to blame earthquakes on "sinfulness, moral laxity, deviation from the Islamic true path," while "only a couple of muffled voices supported the scientific view that earthquakes are a natural phenomenon unaffected by human activity."[9]

Muslim scientists and scholars have subsequently developed a spectrum of viewpoints on the place of scientific learning within the context of Islam.[1]

Muslim Nobel laureates

as of 2018, three Muslim scientists have won a novel prize for science (Abdus Salam from Pakistanin physics, Ahmed Zewail from Egypt and Aziz Sancar from Turkey in Chemistry). According to some (MUSTAFA AKYOL), the relative lack of Muslim Nobel laureates in sciences per capita can be attributed to more insular interpretations of the religion than in the golden age of Islamic discovery and development, when society was more open to foreign ideas.[40]Abdus Salam, who won a Nobel Prize in Physics for his electroweak theory, is among those who argue that the quest for reflecting upon and studying nature is a duty upon Muslims.[41]

Explanations for decline

This section may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. Please help to create a more balanced presentation. Discuss and resolve this issue before removing this message. (August 2017)

|

Others claim traditional interpretations of Islam are not compatible with the development of science. Author Rodney Stark argues that Islam's lag behind the West in scientific advancement after (roughly) 1500 AD was due to opposition by traditional ulema to efforts to formulate systematic explanation of natural phenomenon with "natural laws." He claims that they believed such laws were blasphemous because they limit "Allah's freedom to act" as He wishes, a principle enshired in aya 14:4: "Allah sendeth whom He will astray, and guideth whom He will," which (they believed) applied to all of creation not just humanity.[45]

Taner Edis wrote An Illusion of Harmony: Science and Religion in Islam.[46] Edis worries that secularism in Turkey, one of the most westernized Muslim nations, is on its way out; he points out that Turkey rejects evolution by a large majority. To Edis, many Muslims appreciate technology and respect the role that science plays in its creation. As a result, he says there is a great deal of Islamic pseudoscience attempting to reconcile this respect with other respected religious beliefs. Edis maintains that the motivation to read modern scientific truths into holy books is also stronger for Muslims than Christians.[47] This is because, according to Edis, true criticism of the Qur'an is almost non-existent in the Muslim world. While Christianity is less prone to see its Holy Book as the direct word of God, fewer Muslims will compromise on this idea – causing them to believe that scientific truths simply must appear in the Qur'an. However, Edis opines that there are endless examples of scientific discoveries that could be read into the Bible or Qur'an if one would like to.[47] Edis qualifies that 'Muslim thought' certainly cannot be understood by looking at the Qur'an alone – cultural and political factors play large roles.[47]

Biological evolution

The Quran contains many verses describing creation of the universe; Muslims believe God created the heavens and earth in six days;[7:54] the earth was created in two days,[41:9] and in two other days (into a total of four) God furnished the creation of the earth with mountains, rivers and fruit-gardens[41:10]. The heavens and earth formed from one mass which had to be split[21:30], the heavens used to be smoke[41:11], and form layers, one above the other[67:3]. The angels inhabit the seventh heavens. The lowest heaven is adorned with lights[41:12], the sun and the moon (which follow a regular path)[71:16][14:33], the stars[37:6] and the constellations of the Zodiac[15:16].[48]A faction of Muslims are at odds with current scientific theories about biological evolution and the origin of man. A recent Pew study[49] reveals that in only four of the 22 countries surveyed that at least 50% of the people surveyed rejected evolution. For instance, a relatively large fraction of people accept human evolution in Kazakhstan (79%) and Lebanon (78%), but relatively few in Afghanistan (26%), Iraq (27%), and Pakistan (30%); a total of 13 of the countries surveyed had at least 50% of the population surveyed who agreed with the statement that humans evolved over time. The late Ottoman intellectual Ismail Fennî, while personally rejecting Darwinism, insisted that it should be taught in schools as even false theories contributed to the improvement of science. He held that interpretations of the Quran might require amendment should Darwinism eventually be shown to be true.[50]

See also

- Qur'an and miracles

- Relationship between religion and science

- Religious interpretations of the Big Bang theory

- Ahmadiyya views of evolution

- Bahá'í Faith and science

- Ibn Sina Academy of Medieval Medicine and Sciences

References

- "The British Journal for the History of Science V48:4". Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Qur'an on science |

- Islam & Science

- Science and the Islamic world—The quest for rapprochement by Pervez Hoodbhoy.

- Islamic Science by Ziauddin Sardar (2002).

- Can Science Dispense With Religion? by Mehdi Golshani.

- Islam, science and Muslims by Seyyed Hossein Nasr.

- Islam, Muslims, and modern technology by Seyyed Hossein Nasr.

- Center for Islam and Science

- Explore Islamic achievements and contributions to science

- Is There Such A Thing As Islamic Science? The Influence Of Islam On The World Of Science

- How Islam Won, and Lost, the Lead in Science

- Radicalism among Muslim professionals worries many

Comments

Post a Comment