Jinn

Imam Ali Conquers Jinn, unknown artist, Ahsan-ol-Kobar (1568) Golestan Palace

Contents

Etymology

Jinn is an Arabic collective noun deriving from the Semitic root JNN (Arabic: جَنّ / جُنّ, jann), whose primary meaning is "to hide" or "to conceal". Some authors interpret the word to mean, literally, "beings that are concealed from the senses".[4] Cognates include the Arabic majnūn ("possessed", or generally "insane"), jannah ("garden"), and janīn ("embryo").[5] Jinn is properly treated as a plural, with the singular being jinni.The origin of the word Jinn remains uncertain.[6] Some scholars relate the Arabic term jinn to the Latin genius, as a result of syncretism during the reign of the Roman empire under Tiberius Augustus,[7] but this derivation is also disputed.[8] Another suggestion holds, that jinn may derived from Aramaic "ginnaya" (Classical Syriac: ܓܢܬܐ) with the meaning of Tutelary deity [9] or also ‘garden’. Others claim a Persian origin of the word, for in the form of the Avestic "Jaini", a wicked (female) spirit. Jaini were among various creatures in the possibly even pre-Zoroastrian mythology of peoples of Iran.[10][11]

The anglicized form genie is a borrowing of the French génie, from the Latin genius, a guardian spirit of people and places in Roman religion. It first appeared[12] in 18th-century translations of the Thousand and One Nights from the French,[13] where it had been used owing to its rough similarity in sound and sense.

Pre-Islamic Arabia

Jinn were worshipped by Arabs during the Pre-Islamic period. But unlike gods, jinn were not depicted as immortals, rather assisting humans in regard of their worships. According to a common belief, soothsayers and poets got their inspirations from the jinn.[14] However jinn were also feared and thought to be responsible for various diseases and mental illnesses.[15] Julius Wellhausen has observed that such spirits were thought to inhabit desolate, dingy, and dark places and that they were feared.[16] One had to protect oneself from them, but they were not the objects of a true cult.[16] In ancient Arabia, the term jinn also applied to all kinds of supernatural entities among various religions and cults, thus angels and demons among Zoroastrianism, Christianity and Judaism were also called jinn.[17]Islamic theology

In the Islamic sense, jinn is used in two different ways:- As the opposite of al-Ins (something in shape) referring to any object concealed from humans sensory organs, including angels, demons and the interior of humn. Thus every demon and every angel is also a jinn, but not every jinn is an angel or a demon.[18][19][20]

- An invisible entity, created by God out of a "mixture of fire" or "smokeless fire", who roamed the earth before Adam. These entities are believed to resemble human in regards of the need of eating and drinking, procreation and dying, being subject to judgment and will either condemned to heaven or hell according to their deeds.[21] But they were much faster and stronger than humans.

Another Islamic prophet, who is related to interactions with jinn, is Solomon. In Quran, he is said to be a king in ancient Israel and was gifted by God to talk to animals and jinn. God granted him authory over the rebellious jinn and the demons, thus Solomon forced them to build the First Temple. Beliefs regarding Solomon and his power over the jinn were later extended in folklore and folktales.

Related to common traditions, the angels were created on Wednesday, the jinn on Thursday and humans on Friday, but not the very next day, rather more than 1000 years later. [25] The community of the jinn race were like these of humans, but then corruption and injustice among them increased and all warnings sent by God were ignored. Consequentially, God sent his angels to battle the infidel jinn. Just a few survived, and were oust to far islands or to the mountains. With the revelation of Islam, the jinn were given a new chance to access salvation.[26][27]

Development of Islamic Jinn belief

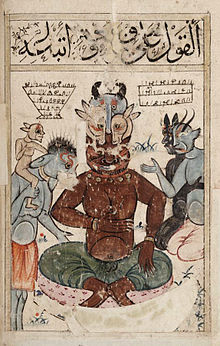

The black king of the djinns, Al-Malik al-Aswad, from the late 14th century Book of Wonders

In the beginning of Islam

In early Islamic development, the status of jinn were reduced from that of deity[28] to minor spirits. To assert a strictly monotheism and the Islamic concept on Tauhid all affinities between the jinn and God were denied, thus Jinn were placed parallel to human, also subject to Gods judgment and may attain paradise or hell. However, even their status as tutelary deities was reduced, they were not consequently regarded as demons.[29] In later revelations, the concept of demons and angels distinct from the pagan jinn were made.[30] T. Fahd stated, the jinn were related to the pagan belief, while the demons and angels were borrowed from monotheistic concepts of angels and demons. In later revealations the demons and the jinn seems to be used interchangeable, here placing the jinn with the devil diametral, against the angels and Muhammad.Jinn belief in the later centuries

When Islam spread outside of Arabia, belief in the Jinn was assimilated with local belief about spirits and deities from Iran, Africa, Turkey and India.[31] Persians, for example, identified the Jinn in the Quran with the Daeva from Zoroastrian lore.[32] Developed from various traditions and local folklore, but not mentioned in canonical Islamic scriptures, Jinn were thought to be able to possess humans; Morocco especially has many possession traditions, including exorcism rituals.[33] In Sindh the concept of the Jinni was introduced during the Abbasid Era and has become a common part of local folklore, also including stories of both male jinn called "Jinn" and female Jinn called "Jiniri". Folk stories of female Jinn include stories such as the Jejhal Jiniri. Although, due to the cultural influence, the concept of jinn may vary over different concepts, all share some common features. The Jinn are believed to live in societies resembling these of humans, practicing religion (including Islam, Christianity and Judaism), having emotions, needing to eat and drink, and can procreate and raise families. Additionally, they fear iron, generally appear in desolate or abandoned places, and are stronger and faster than humans.[34] Generally, Jinn are thought to eat bones and prefer rotten flesh over fresh flesh.[35]The composition and existence of Jinn is the subject of various debates during the Middle Ages. According to Ashari, the existence of Jinn can not be proven, because arguments concerning the existence of jinn are beyond human comprehension. Adepts of Ashʿari theology, explained Jinn are invisible to humans because they lack the appropriate sense organs to envision them.[36] Critics argued, if Jinn exist, their bodies must either be ethereal or made of solid material; if they were composed of the former, they would not able to do hard work, like carrying heavy stones. If they were composed of the latter, they would be visible to any human with functional eyes.[37] Critics therefore refused to believe in a literal reading on Jinn in Islamic sacred texts, preferring to view them as "unruly men".[38] On the other hand, advocates of belief in Jinn assert that God's creation can exceed the human mind; thus, Jinn are beyond human understanding. Since they are mentioned in Islamic texts, scholars such as Ibn Taimiyya and Ibn Hazm prohibit the denial of Jinn. They also refer to spirits and demons among the Christians, Zoroastrians and Jews to "prove" their existence.[39] Ibn Taymiyya believed the Jinn to be generally "ignorant, untruthful, oppressive and treacherous". He held that the Jinn account for much of the "magic" that is perceived by humans, cooperating with magicians to lift items in the air, delivering hidden truths to fortune tellers, and mimicking the voices of deceased humans during seances.[40]

Other critics, such as Jahiz and Mas'udi, stated that sightings of Jinn are due to psychological causes. According to Mas'udi, the Jinn as described by traditional scholars, are not a priori false, but improbable. Jahiz states in his work Kitab al-Hayawan that loneliness induces humans to mind-games and wishful thinking, causing waswās (whisperings in the mind, traditionally thought to be caused by Satan). If he is afraid, he may see things that are not real. These alleged appearances are told to other generations in bedtime stories and poems, and with children of the next generation growing up with such stories, when they are afraid or lonely, they remember these stories, encouraging their imaginations and causing another alleged sighting of Jinn.[41]

Later Sufi traditions related the meaning of Jinn back to its origin "something that is concealed from sights", thus they were related to the hidden realm, including angels from the heavenly realm and the Jinn from an sublunary realm. Ibn Arabi stated: "Only this much is different-the spirits of the Jinn are lower spirits, while the spirits of angels are heavenly spirits.[42] The jinn share, due to their intermediary abode both angelic and human traits. According to some Sufi teachings, a jinn is like an empty cup, composed of its own ego and intention, and a reflection of its observer.[43] Because Jinn are closer to the material realm, it would be easier for human to contact a Jinn, than an angel.[44]

In folk literature

Abbasid manuscript of the One Thousand and One Nights

Modern interpretations

Althought affirmation on the existence of jinn as sapient creatures living along with human is still widespread in Middle Eastern world, modernist commentators, on the basis of the word's meaning, refer jinn to microorganisms such as bacteria and viruses or rather to undetectable uncivilized persons.[50][51] Another interpretation holds, they live in paralleldimensions consisting on rays.In science

18th century Ottoman Manuscript depicting Jinn causing toothaches

Depictions of Jinn

Generally jinn lack individuality and are thought to appear in mists or sandstorms.[54] Zubayr ibn al-Awam, who is held to have accompanied Muhammad during his lecture to the jinn, is said to view the jinn as shadowy ghosts with no individual structure.[55] But jinn are thought to be able to materialize in different forms and therefore may gain individuality, like Sakhr.[56] They can shape into both animals and human. Especially black dogs, onagers and serpents are thought to be common temporarily embodiments of jinn. Except for the 'udhrut from Yemeni folklore, jinn could not transform in wolves, because they were the foes of jinn, disabling the jinn to vanish. [57] Associations between dogs and jinn prevailed in Arabic-literature, but lost its meaning in Persian scriptures.[58] Commonly associated with jinn in humanform are the Si'lah and the Ghoul. However they stay partly animalic, their bodies are depicted as fashioned out of two or more different species.[59] Therefore, individual jinn are commonly depicted as monstrous and anthropomorphized creatures with body parts from different animals or human with animalic traits.[60]Jinn in witchcraft and magical literature

Zawba'a or Zoba'ah, the demon king of Friday

Seven kings of the Jinn are traditionally associated with days of the week.[66]

- Sunday: Al-Mudhib (Abu 'Abdallah Sa'id)

- Monday: Murrah al-Abyad Abu al-Harith (Abu al-Nur)

- Tuesday: Abu Mihriz (or Abu Ya'qub) Al-Ahmar

- Wednesday: Barqan Abu al-'Adja'yb

- Thursday: Shamhurish (al-Tayyar)

- Friday: Abu Hasan Zoba'ah (al-Abyad)

- Saturday: Abu Nuh Maimun

Comparative mythology

Judaism

Shedim, one of several supernatural creatures in early Jewish mythology resemble the Islamic concept of Jinn. Both are said to be invisible to human eye but are subject to bodily desires, like procreating and the need to eat and both may be malevolent or benevolent. Like the Islamic notion of jinn as Pre-Adamites, Jewish lore also regard shedim as Pre-Adamites, replaced by human being in some legends.[68][69] Narrations regarding Asmodeus, an antagonist in Solomon legends, appears both in Islamic lore and in Talmud as the king either of the jinn or the shedim.[3]:120Buddhism

Similar to the Islamic idea of spiritual entities converting to One's religion can be found on Buddhism lore. Accordingly, Buddha preached among humans and Deva, spiritual entities who are like humans subject to the cycle of life.[70][71]In the Guanche mythology

In Guanche mythology from Tenerife in the Canary Islands, there existed the belief in beings that were similar to genies,[72] such as the maxios or dioses paredros ("attendant gods", domestic and nature spirits) and tibicenas (evil genies), as well as the demon Guayota (aboriginal god of evil) that, like the Arabic Iblīs, is sometimes identified with a genie.[73] The Guanches were the Berber natives of the Canary Islands before they were colonised and enslaved by the Europeans who claimed the island for themselves.Christian sources

Van Dyck's Arabic translation of the Old Testament uses the alternative collective plural "jann" (Arab:الجان}; translation:al-jānn) to render the Hebrew word usually translated into English as "familiar spirit" (אוב , Strong #0178) in several places (Leviticus 19:31, 20:6, 1 Samuel 28:3,7,9, 1 Chronicles 10:13).[74]In popular culture

Hungarian stamp representing an emerging Jinni (based on the Arabian Nights)

Genies appear in film in various forms, such as the genie freed by Abu, the eponymous character in the 1940 film Thief of Bagdad.[75]

A Jinn makes a short appearance in the novel American Gods by Neil Gaiman, originally published in 2001. American Gods was also made into a TV series for the Starz television cable television network in 2017. The television adaptation also features a Jinn.

The protagonist of the Bartimaeus Sequence is a jinni, and the books have an established hierarchy that include other types of spirit: imps, foliots, djinn, afrits, and marids (to use the author's own spelling). In this interpretation, jinn and all other spirits are not physical beings, but are instead from another dimension of chaos called "The Other Place". To exist on Earth at all, magicians must summon sprits and force them to take some kind of form, something so alien that it causes all spirits pain. As a result, magicians must put measures in place to force spirits to do what they want in a form of magical slavery.

Gallery

|

|

This section contains what may be an unencyclopedic or excessive gallery of images. (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

-

Zulqarnayn with the help of some jinn, building the Iron Wall to keep the barbarian Gog and Magog from civilized peoples (16th century Persian miniature)

-

The sleeping genie and the lady, from the Arabian Nights, illustrated by Sir John Tenniel, 1912

-

page from 14th/15th-century manuscript Kitab al-Bulhan or Book of Wonders

See also

- Daeva

- Daemon (classical mythology)

- Demonology

- Devil (Islam)

- Djinn (comics)

- Exorcism in Islam

- Fairy

- Genie in popular culture

- Genius loci

- Genius (mythology)

- Ghoul (Jinn who dwell within graveyards)

- Hinn

- Houri

- Ifrit

- Marid

- Nasnas

- Peri

- Qareen

- Qutrub

- Rig-e Jenn

- Shayṭān (Troops of Demons headed by Iblis)

- Shedim

- Sila

- Theriocephaly

- Will of the wisp

- Winged genie

- Yazata

References

- Crowther, Bosley (6 December 1940). "'The Thief of Bagdad,' a Delightful Fairy Tale, at the Music Hall--'Lady With Red Hair,' at the Palace". New York Times. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

Bibliography

- Al-Ashqar, Dr. Umar Sulaiman (1998). The World of the Jinn and Devils. Boulder, CO: Al-Basheer Company for Publications and Translations.

- Barnhart, Robert K. The Barnhart Concise Dictionary of Etymology. 1995.

- "Genie". The Oxford English Dictionary. Second edition, 1989.

- Abu al-Futūḥ Rāzī, Tafsīr-e rawḥ al-jenān va rūḥ al-janān IX-XVII (pub. so far), Tehran, 1988.

- Moḥammad Ayyūb Ṭabarī, Tuḥfat al-gharā’ib, ed. J. Matīnī, Tehran, 1971.

- A. Aarne and S. Thompson, The Types of the Folktale, 2nd rev. ed., Folklore Fellows Communications 184, Helsinki, 1973.

- Abu’l-Moayyad Balkhī, Ajā’eb al-donyā, ed. L. P. Smynova, Moscow, 1993.

- A. Christensen, Essai sur la Demonologie iranienne, Det. Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, Historisk-filologiske Meddelelser, 1941.

- R. Dozy, Supplément aux Dictionnaires arabes, 3rd ed., Leyden, 1967.

- H. El-Shamy, Folk Traditions of the Arab World: A Guide to Motif Classification, 2 vols., Bloomington, 1995.

- Abū Bakr Moṭahhar Jamālī Yazdī, Farrokh-nāma, ed. Ī. Afshār, Tehran, 1967.

- Abū Jaʿfar Moḥammad Kolaynī, Ketāb al-kāfī, ed. A. Ghaffārī, 8 vols., Tehran, 1988.

- Edward William Lane, An Arabic-English Lexicon, Beirut, 1968.

- L. Loeffler, Islam in Practice: Religious Beliefs in a Persian Village, New York, 1988.

- U. Marzolph, Typologie des persischen Volksmärchens, Beirut, 1984. Massé, Croyances.

- M. Mīhandūst, Padīdahā-ye wahmī-e dīrsāl dar janūb-e Khorāsān, Honar o mordom, 1976, pp. 44–51.

- T. Nöldeke "Arabs (Ancient)", in J. Hastings, ed., Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics I, Edinburgh, 1913, pp. 659–73.

- S. Thompson, Motif-Index of Folk-Literature, rev. ed., 6 vols., Bloomington, 1955.

- S. Thompson and W. Roberts, Types of Indic Oral Tales, Folklore Fellows Communications 180, Helsinki, 1960.

- Solṭān-Moḥammad ibn Tāj al-Dīn Ḥasan Esterābādī, Toḥfat al-majāles, Tehran.

- Moḥammad b. Maḥmūd Ṭūsī, Ajāyeb al-makhlūqāt va gharā’eb al-mawjūdāt, ed. M. Sotūda, Tehran, 1966.

Further reading

- Crapanzano, V. (1973) The Hamadsha: a study in Moroccan ethnopsychiatry. Berkeley, CA, University of California Press.

- Drijvers, H. J. W. (1976) The Religion of Palmyra. Leiden, Brill.

- El-Zein, Amira (2009) Islam, Arabs, and the intelligent world of the Jinn. Contemporary Issues in the Middle East. Syracuse, NY, Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-3200-9.

- El-Zein, Amira (2006) "Jinn". In: J. F. Meri ed. Medieval Islamic civilization – an encyclopedia. New York and Abingdon, Routledge, pp. 420–421.

- Goodman, L.E. (1978) The case of the animals versus man before the king of the Jinn: A tenth-century ecological fable of the pure brethren of Basra. Library of Classical Arabic Literature, vol. 3. Boston, Twayne.

- Maarouf, M. (2007) Jinn eviction as a discourse of power: a multidisciplinary approach to Moroccan magical beliefs and practices. Leiden, Brill.

- Taneja, Anand V. (2017) Jinnealogy: Time, Islam, and Ecological Thought in the Medieval Ruins of Delhi. Stanford, CA, Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-1503603936

- Zbinden, E. (1953) Die Djinn des Islam und der altorientalische Geisterglaube. Bern, Haupt.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Genies. |

| Look up genie in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Jinn. |

Comments

Post a Comment