Hittites

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

| Hittite Empire | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

The Hittite Empire, c. 1300 BC (shown in blue)

|

||||||||||

| Capital | Hattusa | |||||||||

| Languages | Hittite, Luwian, Akkadian, many others | |||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy (Old Kingdom) Constitutional monarchy (Middle and New Kingdom)[1] |

|||||||||

| List of Hittite kings | Labarna I (first) | |||||||||

| Suppiluliuma II (last) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age | |||||||||

| • | Established | c. 1600 BC | ||||||||

| • | Disestablished | c. 1178 BC | ||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Today part of | ||||||||||

|

Part of a series on the

|

|---|

| History of Turkey |

|

The Hittite language was a distinct member of the Anatolian branch of the Indo-European language family, and along with the related Luwian language, is the oldest historically attested Indo-European language.[2] They referred to their native land as Hatti. The conventional name "Hittites" is due to their initial identification with the Biblical Hittites in 19th century archaeology. Despite their use of the name Hatti for their core territory, the Hittites should be distinguished from the Hattians, an earlier people who inhabited the same region (until the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC) and spoke an unrelated language known as Hattic.[3]

During the 1920s, interest in the Hittites increased with the founding of the modern Republic of Turkey and attracted the attention of archaeologists such as Halet Çambel and Tahsin Özgüç, leading to the decipherment of Hittite hieroglyphs. During this period, the new field of Hittitology also influenced the naming of institutions, such as the state-owned Etibank ("Hittite bank"),[4] and the foundation of the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara, located 200 kilometers west of the Hittite capital and housing the most comprehensive exhibition of Hittite artifacts in the world.

The history of the Hittite civilization is known mostly from cuneiform texts found in the area of their kingdom, and from diplomatic and commercial correspondence found in various archives in Assyria, Babylonia, Egypt and the Middle East, the decipherment of which was also a key event in the history of Indo-European linguistics. The Hittite military made successful use of chariots,[5] and although belonging to the Bronze Age, the Hittites were the forerunners of the Iron Age, developing the manufacture of iron artifacts from as early as the 18th century BC; at this time, gifts from the "man of Burushanda" of an iron throne and an iron sceptre to the Kaneshite king Anitta were recorded in the Anitta text inscription.

Contents

Archaeological discovery

Bronze religious standard from a pre-Hittite tomb at Alacahöyük, dating to the third millennium BC, from the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara.

Biblical background

Before the discoveries, the only source of information about Hittites had been the Old Testament. Francis William Newman expressed the critical view, common in the early 19th century, that, "no Hittite king could have compared in power to the King of Judah...".[6]As archaeological discoveries revealed the scale of the Hittite kingdom in the second half of the 19th century, Archibald Henry Sayce postulated, rather than to be compared to Judah, the Anatolian civilization "[was] worthy of comparison to the divided Kingdom of Egypt", and was "infinitely more powerful than that of Judah".[7] Sayce and other scholars also noted that Judah and the Hittites were never enemies in the Hebrew texts; in the Book of Kings, they supplied the Israelites with cedar, chariots, and horses, as well as being a friend and ally to Abraham in the Book of Genesis. Uriah (the Hittite) was a captain in King David's army and counted among one of his "mighty men" in 1 Chronicles 11.

Initial discoveries

Bronze Hittite figures of animals in Museum of Anatolian Civilizations.

The first archaeological evidence for the Hittites appeared in tablets found at the Assyrian colony of Kültepe (ancient Karum Kanesh), containing records of trade between Assyrian merchants and a certain "land of Hatti". Some names in the tablets were neither Hattic nor Assyrian, but clearly Indo-European.[8]

The script on a monument at Boğazköy by a "People of Hattusas" discovered by William Wright in 1884 was found to match peculiar hieroglyphic scripts from Aleppo and Hamath in Northern Syria. In 1887, excavations at Tell El-Amarna in Egypt uncovered the diplomatic correspondence of Pharaoh Amenhotep III and his son Akhenaton. Two of the letters from a "kingdom of Kheta"—apparently located in the same general region as the Mesopotamian references to "land of Hatti"—were written in standard Akkadian cuneiform script, but in an unknown language; although scholars could read it, no one could understand it. Shortly after this, Archibald Sayce proposed that Hatti or Khatti in Anatolia was identical with the "kingdom of Kheta" mentioned in these Egyptian texts, as well as with the biblical Hittites. Others, such as Max Müller, agreed that Khatti was probably Kheta, but proposed connecting it with Biblical Kittim, rather than with the "Children of Heth". Sayce's identification came to be widely accepted over the course of the early 20th century; and the name "Hittite" has become attached to the civilization uncovered at Boğazköy.[citation needed]

Sphinx Gate entrance at Hattusa.

Under the direction of the German Archaeological Institute, excavations at Hattusa have been under way since 1907, with interruptions during the world wars. Kültepe was successfully excavated by Professor Tahsin Özgüç from 1948 until his death in 2005. Smaller scale excavations have also been carried out in the immediate surroundings of Hattusa, including the rock sanctuary of Yazılıkaya, which contains numerous rock reliefs portraying the Hittite rulers and the gods of the Hittite pantheon.

Writings

The Hittites used Mesopotamian Cuneiform script. Archaeological expeditions to Hattusa have discovered entire sets of royal archives in cuneiform tablets, written either in the Semitic Mesopotamian Akkadian language of Assyria and Babylonia, the diplomatic language of the time, or in the various dialects of the Hittite confederation.[9]Museums

Jewelry from Museum of Anatolian Civilizations.

Geography

Ceremonial vessels in the shape of sacred bulls, called Hurri (Day) and Seri (Night) found in Hattusha, Hittite Old Kingdom (16th century BC) Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara.

The Hittite Empire at its greatest extent under Suppiluliuma I (c. 1350–1322 BC) and Mursili II (c. 1321–1295 BC)

To the west and south of the core territory lay the region known as Luwiya in the earliest Hittite texts. This terminology was replaced by the names Arzawa and Kizzuwatna with the rise of those kingdoms.[10] Nevertheless, the Hittites continued to refer to the language that originated in these areas as Luwian. Prior to the rise of Kizzuwatna, the heart of that territory in Cilicia was first referred to by the Hittites as Adaniya.[11] Upon its revolt from the Hittites during the reign of Ammuna,[12] it assumed the name of Kizzuwatna and successfully expanded northward to encompass the lower Anti-Taurus mountains as well. To the north, lived the mountainous people called the Kaskians. To the southeast of the Hittites lay the Hurrian empire of Mitanni. At its peak, during the reign of Mursili II, the Hittite empire stretched from Arzawa in the west to Mitanni in the east, many of the Kaskian territories to the north including Hayasa-Azzi in the far north-east, and on south into Canaan approximately as far as the southern border of Lebanon, incorporating all of these territories within its domain.

History

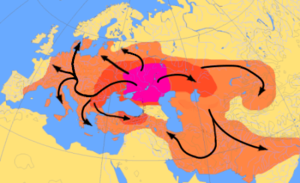

Map of Indo-European migrations from c. 4000 to 1000 BC according to the

Kurgan model. The Anatolian migration (indicated with a dotted arrow)

probably took place across the Balkans. The magenta area corresponds to

the assumed Urheimat (Samara culture, Sredny Stog culture).

The red area corresponds to the area that may have been settled by

Indo-European-speaking peoples up to c. 2500 BC, and the orange area by

1000 BC.

Origins

It is generally assumed that the Hittites came into Anatolia some time before 2000 BC. While their earlier location is disputed, it has been speculated by scholars for more than a century that the Kurgan cultures of the Pontic Steppe, in present-day Ukraine, around the Sea of Azov spoke an early Indo-European language during the third and fourth millennia BC.[13]The arrival of the Hittites in Anatolia in the Bronze Age was one of a superstrate imposing itself on a native culture (in this case over the pre existing Hattians and Hurrians), either by means of conquest or by gradual assimilation.[14][15] In archaeological terms, relationships of the Hittites to the Ezero culture of the Balkans and Maikop culture of the Caucasus have been considered within the migration framework.[16] The Indo-European element at least establishes Hittite culture as intrusive to Anatolia in scholarly mainstream (excepting the opinions of Colin Renfrew,[17][18] whose Anatolian hypothesis assumes that Indo-European is indigenous to Anatolia, and, more recently, Quentin Atkinson[19]).[15]

According to Anthony, steppe herders, archaic Proto-Indo-European speakers, spread into the lower Danube valley about 4200-4000 BC, either causing or taking advantage of the collapse of Old Europe.[20] Their languages "probably included archaic Proto-Indo-European dialects of the kind partly preserved later in Anatolian."[21] Their descendants later moved into Anatolia at an unknown time but maybe as early as 3000 BC.[22] According to J. P. Mallory it is likely that the Anatolians reached the Near East from the north either via the Balkans or the Caucasus in the 3rd millennium BC.[23] According to Parpola, the appearance of Indo-European speakers from Europe into Anatolia, and the appearance of Hittite, is related to later migrations of Proto-Indo-European speakers from the Yamna-culture into the Danube Valley at ca. 2800 BC,[24][25] which is in line with the "customary" assumption that the Anatolian Indo-European language was introduced into Anatolia somewhere in the third millennium BC.[26]

Their movement into the region may have set off a Near East mass migration sometime around 1900 BC.[citation needed] The dominant indigenous inhabitants in central Anatolia at the time were Hurrians and Hattians who spoke non-Indo-European languages (some have argued that Hattic was a Northwest Caucasian language, but its affiliation remains uncertain), whilst the Hurrian language was a near-Isolate (i.e. it was one of only two or three languages in the Hurro-Urartian family). There were also Assyrian colonies in the region during the Old Assyrian Empire (2025-1750 BC); it was from the Semitic Assyrians of Upper Mesopotamia that the Hittites adopted the cuneiform script. It took some time before the Hittites established themselves following the collapse of the Old Assyrian Empire in the mid-18th century BC, as is clear from some of the texts included here. For several centuries there were separate Hittite groups, usually centered on various cities. But then strong rulers with their center in Hattusas (modern Boğazköy) succeeded in bringing these together and conquering large parts of central Anatolia to establish the Hittite kingdom.[27]

Early Period

Hittite chariot, from an Egyptian relief

Zalpa first attacked Kanesh under Uhna in 1833 BC.[30]

One set of tablets, known collectively as the Anitta text,[31] begin by telling how Pithana the king of Kussara conquered neighbouring Neša (Kanesh).[32] However, the real subject of these tablets is Pithana's son Anitta (r. 1745–1720 BC),[33] who continued where his father left off and conquered several northern cities: including Hattusa, which he cursed, and also Zalpuwa (Zalpa). This was likely propaganda for the southern branch of the royal family, against the northern branch who had fixed on Hattusa as capital.[34] Another set, the Tale of Zalpa, supports Zalpa and exonerates the later Hattusili I from the charge of sacking Kanesh.[34]

Anitta was succeeded by Zuzzu (r. 1720–1710 BC);[33] but sometime in 1710–1705 BC, Kanesh was destroyed taking the long-established Assyrian merchant trading system with it.[30] A Kussaran noble family survived to contest the Zalpuwan / Hattusan family, though whether these were of the direct line of Anitta is uncertain.[35]

Meanwhile, the lords of Zalpa lived on. Huzziya I, descendant of a Huzziya of Zalpa, took over Hatti. His son-in-law Labarna I, a southerner (of Hurma) usurped the throne but made sure to adopt Huzziya's grandson Hattusili as his own son and heir.

Old Kingdom

Hattusa ramp

Mursili continued the conquests of Hattusili I. Mursili's conquests reached southern Mesopotamia and even ransacked Babylon itself in 1531 BC (short chronology).[39] Rather than incorporate Babylonia into Hittite domains, Mursili seems to have instead turned control of Babylonia over to his Kassite allies, who were to rule it for the next four centuries. This lengthy campaign, however, strained the resources of Hatti, and left the capital in a state of near-anarchy. Mursili was assassinated shortly after his return home, and the Hittite Kingdom was plunged into chaos. The Hurrians (under the control of an Indo-Aryan Mitanni ruling class), a people living in the mountainous region along the upper Tigris and Euphrates rivers in modern south east Turkey, took advantage of the situation to seize Aleppo and the surrounding areas for themselves, as well as the coastal region of Adaniya, renaming it Kizzuwatna (later Cilicia).

Following this, the Hittites entered a weak phase of obscure records, insignificant rulers, and reduced area of control. This pattern of expansion under strong kings followed by contraction under weaker ones, was to be repeated over and over again throughout the Hittite Kingdom's 500-year history, making events during the waning periods difficult to reconstruct with much precision. The political instability of these years of the Old Hittite Kingdom, can be explained in part by the nature of the Hittite kingship at that time. During the Old Hittite Kingdom period prior to 1400 BC, the king of the Hittites was not viewed by the Hittite citizenry as a "living god", like the Pharaohs of Egypt, but rather as a first among equals.[40] Only in the later period of the Hittite Empire, from 1400 BC until 1200 BC, did the kingship of the Hittites become more centralized and powerful. Also in earlier years the succession was not legally fixed, enabling the "war of the Roses" style rivalries between northern and southern branches.

The next monarch of any note following Mursili I was Telepinu (c. 1500 BC), who won a few victories to the southwest, apparently by allying himself with one Hurrian state (Kizzuwatna) against another (Mitanni). Telepinu also attempted to secure the lines of succession.[41]

Middle Kingdom

Twelve Hittite gods of the Underworld in the nearby Yazılıkaya, a sanctuary of Hattusa.

It segues into the "Hittite Empire period" proper, which dates from the reign of Tudhaliya I from c. 1430 BC.

One innovation that can be credited to these early Hittite rulers is the practice of conducting treaties and alliances with neighboring states; the Hittites were thus among the earliest known pioneers in the art of international politics and diplomacy. This is also when the Hittite religion adopted several gods and rituals from the Hurrians.

New Kingdom

Tudhaliya IV (relief in Hattusa)

Hittite monument, an exact replica of monument from Fasıllar in Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara.

During his reign (c. 1400 BC), King Tudhaliya I, again allied with Kizzuwatna, then vanquished the Hurrian states of Aleppo and Mitanni, and expanded to the west at the expense of Arzawa (a Luwian state).

Another weak phase followed Tudhaliya I, and the Hittites' enemies from all directions were able to advance even to Hattusa and raze it. However, the Kingdom recovered its former glory under Suppiluliuma I (c. 1350 BC), who again conquered Aleppo, Mitanni was reduced to vassalage by the Assyrians under his son-in-law, and he defeated Carchemish, another Amorite city-state. With his own sons placed over all of these new conquests, Babylonia still in the hands of the allied Kassites, this left Suppiluliuma the supreme power broker in the known world, alongside Assyria and Egypt, and it was not long before Egypt was seeking an alliance by marriage of another of his sons with the widow of Tutankhamen. Unfortunately, that son was evidently murdered before reaching his destination, and this alliance was never consummated. However, the Middle Assyrian Empire (1365-1050 BC) once more began to grow in power also, with the ascension of Ashur-uballit I in 1365 BC. Ashur-uballit I attacked and defeated Mattiwaza the Mitanni king despite attempts by the Hittite king Suppiluliumas I, now fearful of growing Assyrian power, attempting to preserve his throne with military support. The lands of the Mitanni and Hurrians were duly appropriated by Assyria, enabling it to encroach on Hittite territory in eastern Asia Minor, and Adad-nirari I annexed Carchemish and north east Syria from the control of the Hittites.[44]

After Suppiluliumas I, and a very brief reign by his eldest son, another son, Mursili II became king (c. 1330). Having inherited a position of strength in the east, Mursili was able to turn his attention to the west, where he attacked Arzawa and a city known as Millawanda (Miletus) which was under the control of Ahhiyawa. More recent research based on new readings and interpretations of the Hittite texts, as well as of the material evidence for Mycenaean contacts with the Anatolian mainland, came to the conclusion that Ahhiyawa referred to Mycenaean Greece, or at least to a part of it.[45]

Battle of Kadesh

Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses II storming the Hittite fortress of Dapur.

Downfall and demise of the Kingdom

Egypto-Hittite Peace Treaty (c. 1258 BC) between Hattusili III and Ramesses II. Istanbul Archaeology Museum

Chimera with a human head and a lion's head; Late Hittite period in Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara.

Hattusili's son, Tudhaliya IV, was the last strong Hittite king able to keep the Assyrians out of the Hittite heartland to some degree at least, though he too lost much territory to them, and was heavily defeated by Tukulti-Ninurta I of Assyria in the Battle of Nihriya. He even temporarily annexed the Greek island of Cyprus, before that too fell to Assyria. The very last king, Suppiluliuma II also managed to win some victories, including a naval battle against Alashiya off the coast of Cyprus.[49] But the Assyrians, under Ashur-resh-ishi I had by this time annexed much Hittite territory in Asia Minor and Syria, driving out and defeating the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar I in the process, who also had eyes on Hittite lands. The Sea Peoples had already begun their push down the Mediterranean coastline, starting from the Aegean, and continuing all the way to Canaan, founding the state of Philistia—taking Cilicia and Cyprus away from the Hittites en route and cutting off their coveted trade routes. This left the Hittite homelands vulnerable to attack from all directions, and Hattusa was burnt to the ground sometime around 1180 BC following a combined onslaught from new waves of invaders, the Kaskas, Phrygians and Bryges. The Hittite Kingdom thus vanished from historical records, much of the territory being seized by Assyria.[50] The end of the kingdom was part of the larger Bronze Age Collapse.

Syro-Hittite Kingdoms

Neo-Hittite storm god "Tarhunzas" in Aleppo museum.

Although the Hittite kingdom disappeared from Anatolia at this point, there emerged a number of so-called Neo-Hittite kingdoms in Anatolia and northern Syria. They were the successors of the Hittite Kingdom. The most notable Syrian Neo-Hittite kingdoms were those at Carchemish and Milid (near the later Melitene). These Neo-Hittite Kingdoms gradually fell under the control of the Neo Assyrian Empire (911–608 BC). Carchemish and Milid were made vassals of Assyria under Shalmaneser III (858–823 BC), and fully incorporated into Assyria during the reign of Sargon II (722–705 BC).

A large and powerful state known as Tabal occupied much of southern Anatolia. Known as Gk. Τιβαρηνοί Tibarenoi, Lat. Tibareni, Thobeles in Josephus, their language may have been Luwian,[51] testified to by monuments written using Luwian hieroglyphics.[52] This state too was conquered and incorporated into the vast Assyrian Empire.

Ultimately, both Luwian hieroglyphs and cuneiform were rendered obsolete by an innovation, the alphabet, which seems to have entered Anatolia simultaneously from the Aegean (with the Bryges, who changed their name to Phrygians), and from the Phoenicians and neighboring peoples in Syria.

Government

The head of the Hittite state was the king, followed by the heir-apparent. The king was the supreme ruler of the land, in charge of being a military commander, judicial authority, as well as a high priest.[53] However, some officials exercised independent authority over various branches of the government. One of the most important of these posts in the Hittite society was that of the Gal Mesedi (Chief of the Royal Bodyguards).[54] It was superseded by the rank of the Gal Gestin (Chief of the Wine Stewards), who, like the Gal Mesedi, was generally a member of the royal family. The kingdom's bureaucracy was headed by the Gal Dubsar (Chief of the Scribes), whose authority didn't extend over the Lugal Dubsar, the king's personal scribe.In Egyptian inscriptions dating back before the days of the Exodus, Egyptian monarchs were engaged with two chief seats, located at Kadesh (a Hittite city located on the Orontes River) and Carchemish (located on the Euphrates river in Southern Anatolia).[55]

A map Illustrating Hittite Expansion and location of the Capital City Hattusa

Religion in Early Hittite Government to establish control

In the Central Anatolian settlement of Ankuwa, home of the pre-Hittite goddess Kattaha and the worship of other Hattic deities illustrates the ethnic differences in the areas the Hittites tried to control. Kattaha was originally given the name Hannikkun. The usage of the term Kattaha over Hannikkun, according to Ronald Gorny (head of the Alisar regional project in Turkey), was a device to downgrade the Pre-Hittite identity of this female deity, and to bring her more in touch with the Hittite tradition. Their reconfiguration of Gods throughout their early history such as with Kattaha was a way of legitimizing their authority and to avoid conflicting ideologies in newly included regions and settlements. By transforming local deities to fit their own customs, the Hittites hoped that the traditional beliefs of these communities would understand and accept the changes to become better suited for the Hittite political and economic goals.[56]Political dissent in the Old Kingdom

In 1595 BC, King Marsilis I (r. 1556–1526 BC) marched into the city of Babylon and sacked the city. Due to fear of revolts at home he did not remain there long, quickly returning to his capital of Hattusa. On his journey back to Hattusa he was assassinated by his brother-in-law Hantili I who then took the throne. Hantili was able to escape multiple murder attempts on himself, however, his family did not. His wife, Harapsili and her son were murdered. In addition, other members of the royal family were killed by Zindata I who was then murdered by his own son, Ammunna. All of the internal unrest among the Hittite royal family led to a decline of power. This led to surrounding kingdoms, such as the Hurrians, to have success against Hittite forces and be the center of power in the Anatolian region.[57]The Pankus

King Telipinus (reigned c. 1525 – c. 1500 BC) is considered to be the last king of the Old Kingdom of the Hittites. He seized power during a dynastic power struggle. During his reign, he wanted to take care of lawlessness and regulate royal succession. He then issued the Edict of Telipinus. Within this edict, he designated the pankus, which was a "general assembly", that acted as a high court. Crimes such as murder were observed and judged by the Pankus. Kings were also subject to jurisdiction under the Pankus. The Pankus also served as an advisory council for the king. The rules and regulations set out by the Edict and the establishment of the Pankus proved to be very successful and lasted all the way through to the new Kingdom in the 14th century BC.[58]The Pankus established a legal code where violence was not a punishment for a crime. Crimes such as a murder and theft, which were punishable by death in other southwest Asian Kingdoms at this time, were not under the Hittite law code. Most penalties for crimes involved restitution. For example, in cases of thievery, the punishment of that crime would to be to repay what was stolen in equal value.[59]

Language

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

Bronze tablet from Çorum-Boğazköy dating from 1235 BC. Photographed at Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara.

The language of the Hattusa tablets was eventually deciphered by a Czech linguist, Bedřich Hrozný (1879–1952), who, on 24 November 1915, announced his results in a lecture at the Near Eastern Society of Berlin. His book about the discovery was printed in Leipzig in 1917, under the title The Language of the Hittites; Its Structure and Its Membership in the Indo-European Linguistic Family.[60] The preface of the book begins with:

- "The present work undertakes to establish the nature and structure of the hitherto mysterious language of the Hittites, and to decipher this language [...] It will be shown that Hittite is in the main an Indo-European language."

According to Craig Melchert, the current tendency is to suppose that Proto-Indo-European evolved, and that the "prehistoric speakers" of Anatolian became isolated "from the rest of the PIE speech community, so as not to share in some common innovations."[61] Hittite, as well as its Anatolian cousins, split off from Proto-Indo-European at an early stage, thereby preserving archaisms that were later lost in the other Indo-European languages.[62]

In Hittite there are many loanwords, particularly religious vocabulary, from the non-Indo-European Hurrian and Hattic languages. The latter was the language of the Hattians, the local inhabitants of the land of Hatti before being absorbed or displaced by the Hittites. Sacred and magical texts from Hattusa were often written in Hattic, Hurrian, and Luwian, even after Hittite became the norm for other writings.

Religion and mythology

Stag statuette, symbol of a Hittite male god in Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara. This figure is used for the Hacettepe University emblem.

Storm gods were prominent in the Hittite pantheon. Tarhunt (Hurrian's Teshub) was referred to as 'The Conqueror', 'The king of Kummiya', 'King of Heaven', 'Lord of the land of Hatti'. He was chief among the gods and his symbol is the bull. As Teshub he was depicted as a bearded man astride two mountains and bearing a club. He was the god of battle and victory, especially when the conflict involved a foreign power.[63] Teshub was also known for his conflict with the serpent Illuyanka.[64]

Biblical Hittites

The Bible refers to "Hittites" in several passages, ranging from Genesis to the post-Exilic Ezra-Nehemiah. Genesis 10 (the Table of Nations) links them to an eponymous ancestor Heth, a descendant of Ham through his son Canaan. The Hittites are thereby counted among the Canaanites. The Hittites are usually depicted as a people living among the Israelites—Abraham purchases the Patriarchal burial-plot of Machpelah from "Ephron HaChiti", Ephron the Hittite; and Hittites serve as high military officers in David's army. In 2 Kings 7:6, however, they are a people with their own kingdoms (the passage refers to "kings" in the plural), apparently located outside geographic Canaan, and sufficiently powerful to put a Syrian army to flight.[65]It is a matter of considerable scholarly debate whether the biblical "Hittites" signified any or all of: 1) the original Hattians; 2) their Indo-European conquerors, who retained the name "Hatti" for Central Anatolia, and are today referred to as the "Hittites" (the subject of this article); or 3) a Canaanite group who may or may not have been related to either or both of the Anatolian groups, and who also may or may not be identical with the later Neo-Hittite (Luwian) polities.[66]

Other biblical scholars (following Max Müller) have argued that, rather than being connected with Heth, son of Canaan, the Anatolian land of Hatti was instead mentioned in Old Testament literature and apocrypha as "Kittim" (Chittim), a people said to be named for a son of Javan.[citation needed]

See also

References

- Woudstra, Marten H. (1981). The Book of Joshua. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 60. ISBN 9780802825254. Retrieved 10 March 2014. and Trevor Bryce, The Kingdom of the Hittites, p. 389 ff.

Sources

- Anthony, David W. (2007), The Horse The Wheel And Language. How Bronze-Age Riders From the Eurasian Steppes Shaped The Modern World, Princeton University Press

- Mallory, J.P.; Adams, D.Q. (1997), Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, Taylor & Francis

- Parpola, Asko (2015), The Roots of Hinduism. The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization, Oxford University Press

Literature

| Library resources about the Hittites |

- Akurgal, Ekrem (2001) The Hattian and Hittite Civilizations, Publications of the Republic of Turkey, Ministry of Culture, ISBN 975-17-2756-1

- Bryce, Trevor R. (2002) Life and Society in the Hittite World, Oxford.

- Bryce, Trevor R. (1999) The Kingdom of the Hittites, Oxford.

- Ceram, C. W. (2001) The Secret of the Hittites: The Discovery of an Ancient Empire. Phoenix Press, ISBN 1-84212-295-9.

- Forlanini, Massimo (2010). "An Attempt at Reconstructing the Branches of the Hittite Royal Family of the Early Kingdom Period". In Cohen, Yoram; Gilan, Amir; Miller, Jared L. Pax Hethitica: Studies on the Hittites and Their Neighbours in Honour of Itamar Singer. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Güterbock, Hans Gustav (1983) "Hittite Historiography: A Survey," in H. Tadmor and M. Weinfeld eds. History, Historiography and Interpretation: Studies in Biblical and Cuneiform Literatures, Magnes Press, Hebrew University pp. 21–35.

- Macqueen, J. G. (1986) The Hittites, and Their Contemporaries in Asia Minor, revised and enlarged, Ancient Peoples and Places series (ed. G. Daniel), Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0-500-02108-2.

- Mendenhall, George E. (1973) The Tenth Generation: The Origins of the Biblical Tradition, The Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-1654-8.

- Neu, Erich (1974) Der Anitta Text, (StBoT 18), Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden.

- Orlin, Louis L. (1970) Assyrian Colonies in Cappadocia, Mouton, The Hague.

- Hoffner, Jr., H.A (1973) "The Hittites and Hurrians," in D. J. Wiseman Peoples of the Old Testament Times, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- Gurney, O.R. (1952) The Hittites, Penguin, ISBN 0-14-020259-5

- Kloekhorst, Alwin (2007), Etymological Dictionary of the Hittite Inherited Lexicon, ISBN 978-90-04-16092-7

- Patri, Sylvain (2007), L'alignement syntaxique dans les langues indo-européennes d'Anatolie, (StBoT 49), Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden, ISBN 978-3-447-05612-0

- Bryce, Trevor R. (1998). The Kingdom of the Hittites. Oxford. (Also: 2005 hard and softcover editions with much new material)

- Jacques Freu et Michel Mazoyer, Des origines à la fin de l'ancien royaume hittite, Les Hittites et leur histoire Tome 1, Collection Kubaba, L'Harmattan, Paris, 2007 ;

- Jacques Freu et Michel Mazoyer, Les débuts du nouvel empire hittite, Les Hittites et leur histoire Tome 2, Collection Kubaba, L'Harmattan, Paris, 2007 ;

- Jacques Freu et Michel Mazoyer, L'apogée du nouvel empire hittite, Les Hittites et leur histoire Tome 3, Collection Kubaba, L'Harmattan, Paris, 2008.

- Jacques Freu et Michel Mazoyer, Le déclin et la chute de l'empire Hittite, Les Hittites et leur histoire Tome 4, Collection Kubaba, L'Harmattan, Paris 2010.

- Jacques Freu et Michel Mazoyer, Les royaumes Néo-Hittites, Les Hittites et leur histoire Tome 5, Collection Kubaba, L'Harmattan, Paris 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hittite Empire. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Hittites. |

- Video lecture at Oriental Institute – Tracking the Frontiers of the Hittite Empire

- Hattusas/Bogazköy

- Arzawa, to the west, throws light on Hittites

- Pictures of Boğazköy, one of a group of important sites

- Pictures of Yazılıkaya, one of a group of important sites

- Der Anitta Text (at TITUS)

- Tahsin Ozguc

- Hittites.info

- Hittite Period in Anatolia

- Hethitologieportal Mainz, by the Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mainz, corpus of texts and extensive bibliographies on all things Hittite

- hittites area in cappadocia

- Uşaklı Höyük

Literature

| Library resources about the Hittites |

- Akurgal, Ekrem (2001) The Hattian and Hittite Civilizations, Publications of the Republic of Turkey, Ministry of Culture, ISBN 975-17-2756-1

- Bryce, Trevor R. (2002) Life and Society in the Hittite World, Oxford.

- Bryce, Trevor R. (1999) The Kingdom of the Hittites, Oxford.

- Ceram, C. W. (2001) The Secret of the Hittites: The Discovery of an Ancient Empire. Phoenix Press, ISBN 1-84212-295-9.

- Forlanini, Massimo (2010). "An Attempt at Reconstructing the Branches of the Hittite Royal Family of the Early Kingdom Period". In Cohen, Yoram; Gilan, Amir; Miller, Jared L. Pax Hethitica: Studies on the Hittites and Their Neighbours in Honour of Itamar Singer. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Güterbock, Hans Gustav (1983) "Hittite Historiography: A Survey," in H. Tadmor and M. Weinfeld eds. History, Historiography and Interpretation: Studies in Biblical and Cuneiform Literatures, Magnes Press, Hebrew University pp. 21–35.

- Macqueen, J. G. (1986) The Hittites, and Their Contemporaries in Asia Minor, revised and enlarged, Ancient Peoples and Places series (ed. G. Daniel), Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0-500-02108-2.

- Mendenhall, George E. (1973) The Tenth Generation: The Origins of the Biblical Tradition, The Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-1654-8.

- Neu, Erich (1974) Der Anitta Text, (StBoT 18), Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden.

- Orlin, Louis L. (1970) Assyrian Colonies in Cappadocia, Mouton, The Hague.

- Hoffner, Jr., H.A (1973) "The Hittites and Hurrians," in D. J. Wiseman Peoples of the Old Testament Times, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- Gurney, O.R. (1952) The Hittites, Penguin, ISBN 0-14-020259-5

- Kloekhorst, Alwin (2007), Etymological Dictionary of the Hittite Inherited Lexicon, ISBN 978-90-04-16092-7

- Patri, Sylvain (2007), L'alignement syntaxique dans les langues indo-européennes d'Anatolie, (StBoT 49), Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden, ISBN 978-3-447-05612-0

- Bryce, Trevor R. (1998). The Kingdom of the Hittites. Oxford. (Also: 2005 hard and softcover editions with much new material)

- Jacques Freu et Michel Mazoyer, Des origines à la fin de l'ancien royaume hittite, Les Hittites et leur histoire Tome 1, Collection Kubaba, L'Harmattan, Paris, 2007 ;

- Jacques Freu et Michel Mazoyer, Les débuts du nouvel empire hittite, Les Hittites et leur histoire Tome 2, Collection Kubaba, L'Harmattan, Paris, 2007 ;

- Jacques Freu et Michel Mazoyer, L'apogée du nouvel empire hittite, Les Hittites et leur histoire Tome 3, Collection Kubaba, L'Harmattan, Paris, 2008.

- Jacques Freu et Michel Mazoyer, Le déclin et la chute de l'empire Hittite, Les Hittites et leur histoire Tome 4, Collection Kubaba, L'Harmattan, Paris 2010.

- Jacques Freu et Michel Mazoyer, Les royaumes Néo-Hittites, Les Hittites et leur histoire Tome 5, Collection Kubaba, L'Harmattan, Paris 2012.

At the very least, perhaps we can say that the Ahhiyawa Problem/Question has been solved and answered after all, for there is now little doubt that Ahhiyawa was a reference by the Hittites to some or all of the Bronze Age Mycenaean world.

Comments

Post a Comment